It’s New Year’s Eve and I’m skinning uphill in the dark on a dead man’s skis. The rest of my group is ahead, I could see their headlamps before they turned the corner on the old logging road and continued onward. I’d pulled over to fiddle with the ancient Silvretta bindings that my mountaineering boots kept sliding out of, and now I’m alone in the darkness as a few stray flakes dance down in the beam of my light.

I’ve always loved used skis. First, it was out of necessity, and then later out of nostalgia. I’d see a classic pair of skis at a thrift store and buy them impulsively, just to ski them a few days and find out what all the hype had been about when they first entered the market.

I bought my first pair of touring skis second-hand from a friend who had put many miles and hundreds of thousands of feet of vert on them. They’d been up and down too many mountains to count, and I’d think of those past summits as I struggled to learn how to make a kick turn. I broke them early in the first fall I had them, snapped a tip, but I skied them all winter anyway, falling down couloirs every time I tried to weigh that floppy tip.

I feel the same way when I sell skis too. I’m always tempted to tell the buyers more of their history than they want. “One mount, no core shots, this was the ski I was riding when I didn’t get the girl.” Or “108mm underfoot, very light, I carried this ski on my back for 18 miles of downed trees and crappy trail only to get turned around before the summit because it was too wide for my ski crampons.” I’ll never sell my current touring skis, even once they’re well past their prime and are fully retired. They carry too much weight of memory, too many summits, too many firsts for me to give them up. Every ski has secrets to tell, stories stacked in its core with every turn past owners have made.

But these skis, this owner...he’s gone now, passed away in the summer. I met him once, briefly. He didn’t strike me as a hardcore skier, just a man dedicated to his community, in love with the place he lived and the people he shared it with.

His skis were listed on Facebook a week later. The seller didn’t know anything about them, just that they were his, and that they were taking up room in her garage. I bought them because of the bindings. I love old Silvrettas, they distill the fundamentals of what it takes to walk uphill on skis into one delightfully retro design. And you can ski them with alpine boots or AT boots or mountaineering boots or ice climbing boots. They’re truly versatile.

When I came to pick up the skis she didn’t have an asking price, just wanted them gone, wanted them used, she said their previous owner would have liked that. So I gave her all the cash in my wallet, and as I loaded them, she asked if I wanted any of the rest of his stuff? There was an old nordic setup, a pair of too-long poles, and an ancient skill saw. Monuments to a life apparently. I don’t have the same affinity for old power tools that I have for old skis, they’re more likely to take your finger off.

And then the dead man’s skis sat in my garage getting dusty until I toured too hard during the day before New Year’s Eve, and I couldn’t imagine jamming my feet back into my ski boots for our midnight celebration in the mountains, so I slipped on my ice climbing boots and put some too-long, much-too-wide skins on the bottom of the dead man’s skis.

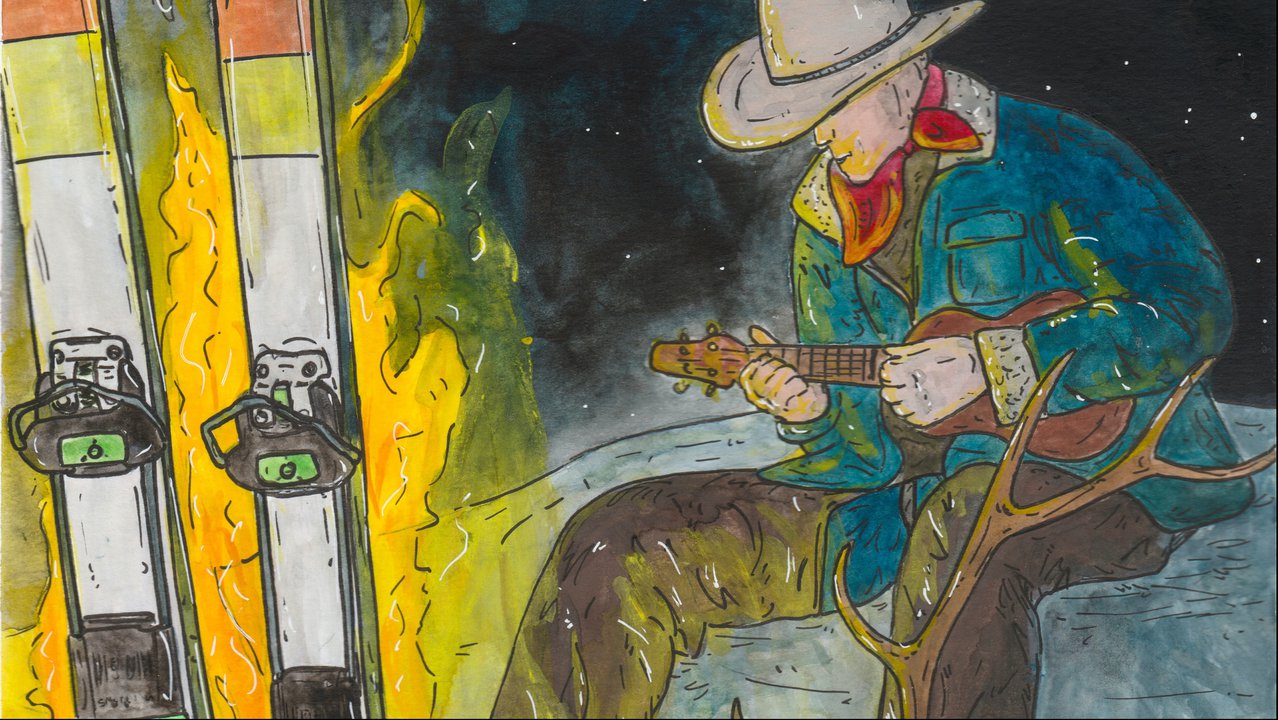

We built a fire and shared champagne on the noll, looking out over the valley and cataloging our highlights from the last year, spitting our goals for the next into the fire, willing them made real by daring to articulate them.

By the end, my feet were cold and numb inside my boots as I clipped into the skis for the mellow mile-long descent back to the car. I’d skied this logging road on my own skis before, and hadn’t needed to turn the whole way, but this was different. As I careened out of control, trying to flex my ridiculously soft boots without ejecting, I couldn’t help wondering what the skis thought of the shitshow happening above them.

When a friend complains about their touring gear, we like to joke that “the Grand was skied on less” because well, it was. Those pioneers climbed and skied so many peaks on gear that made my Silvrettas look state of the art. So it’s not the skis’ fault that I’m crashing into the snowbank, empy champagne bottles clanking on my back. This usec to be a great touring setup, as capable as anything on the market.

I can’t stop wondering why he owned these skis. Was he once a young man hungry to notch up big descents in the Tetons? Have these skis hop turned down lines I’ll never even lay eyes on? Or maybe he just skied the pass a few times a month, wandering up Mail Cabin to wiggle down Windy Ridge? Or maybe he never even skied them downhill, maybe he just used them to walk a dog down the snowy canyon?

I’ll never know, but I like to imagine that these skis and bindings are ripe with ancient memories of sunrise on unfamiliar peaks, and deep, stable snow in tight couloirs. I like to imagine when I finally muscled my mountaineering boots into an angle where I could get the skis on edge that they responded familiarly. Every ski knows how to make a turn, and these had been lingering for years waiting for me to lay over that one tenuous parallel arc that shifted back across the slope into another and another. Maybe they’re just skis, a sandwich of wood and metal and resin and plastic. But the dead man’s skis are more than that, and I’ll think about him every time I click into them.

Comments