Words & photos: Justin Long

Being so exhausted from the last five days, I woke up late and found myself oversleeping at 4:15am. I jolted up, put on my boots, and bolted for the campfire just 50 feet away. Everyone was awake and I’m sure the porters couldn’t sleep in the freezing cold. Three of them were still huddled around the fire exactly like the night before.

My guides Enok and Benard were already waiting for me. I grabbed my pack, skis, crampons, poles, rope and harness and got on the trail as fast as I could. As we started walking, I looked up into the sky and I saw the silhouette of the biggest, edgiest rock I had ever seen.

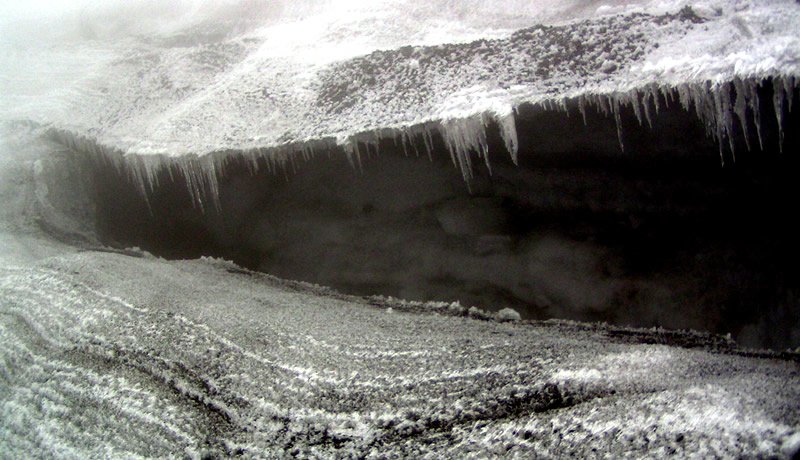

At 6am daylight broke and we arrived at Elena Hut, a green high-altitude hut owned by another company. It’s a colder sleep at Elena, and I’m glad I didn’t spend the night there. Directly above Elena we needed to ascend a cliff of at least 200 feet. This dangerous cliff has been the legacy of Mt. Stanley ascents since the major landslide in the last decade. A safer route was ripped away when the northern face of the lower mountain collapsed destroying the easiest route to the summit. We braced ourselves using rope and climbed.

After we reached the top of the cliff above Elena Hut, we all realized that an amateur from another company had set up the safety ropes. It looked like the rope was going to fail soon. Glad it wasn’t me.

The weather spewed out another menacing storm at us. We were quickly enshrouded in clouds and it started to rain. We reached another cliff that we needed to climb, this time without ropes. For some reason I peered over my shoulder to look below; the fog briefly parted for me to see myself kiddy-cornered next to a thousand-foot drop. I had no idea how I got myself into this situation. I lit a fire in my ass and focused on getting to the top, blurring every other distraction.

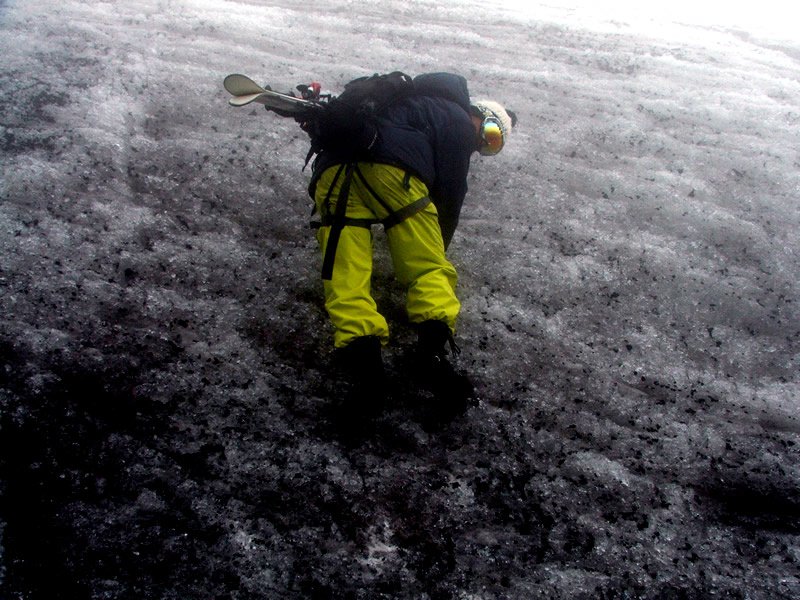

After ascending more slippery rocks, the rain turned to ice and we finally found ourselves at the start of the Stanley Plateau Glacier. We put on our harness and crampons, my ski pants tucked tightly. I laughed at how geeky I looked, but this was just another part of the job. To get to the top of the glacier, we needed to ascend a wall that led to the top of the ice.

We were now on top of the glacier and we began the final ascent. After a brief huddle, we started glacial travel all roped together. Enok led the group, I took the middle, and Benard was last. After only 10 minutes, we realized that the warm weather from the last rainy season wasted the glacier. We were surrounded by crevasses. Hundreds of them.

The dangerous situation left us with two final goals: 1) reach the top of Stanley Plateau, and 2) find a safe spot to ski. The weather was now a thick soup and all of my gear was soaked from a constant ice-rain tug-of-war. We did not get lucky with snow; sometimes the glacier will get a fresh foot of snow every week. We were gifted with concrete ice. But I’m not upset at all.

After we reached the top of the glacier, we plotted a safe area where we could start having fun. I quickly put on my gear for a moment I had anticipated for a long time.

I then got up on my skis.

And whipped out the Newschoolers flag nicely made by Ugandan tailors.

I also had a couple other flags I needed to whip out, too. The Snow4Innocents Crazy Idea Contest had been commanded by a bunch of Canucks fans. So I also skied Mt. Stanley carrying an African-made Canucks flag, too.

And a sponsoring children’s hospital from Oakland also sent me some very small flags.

This isn’t the end of story by any means. Uganda kept flinging more stuff my way.

Our descent was much more dangerous than our earlier ascent. The rocks had become colder and wetter, and we were slipping with every step. We had to use a couple of extra ropes to repel down the cliffs; a slipknot was the only thing between me and the ground.

But we did get a sweet opportunity when the clouds broke during our descent. We got to see the other peaks around us. Here are some shots with Mt. Baker and other Rwenzori peaks in the background.

Enok & Benard

We later found out that around the time we were making our descent, rebels had entered a village just 10km from one of our lower camps. They stole all valuables and killed 9 people in the chaos. They apparently camped near us the whole time.

One of the last camps we used during the descent was a beauty. With a 50-foot ledge hanging over our heads, we had no worry for mud or rain. But we did keep an eye out for leopards.

After eight days we made it back to the bottom. We arrived in the town of Kilembe after 8 days, 80km on foot, and a maximum altitude of at least 5000m (16,000ft).

I grabbed a Ugandan taxi back to the town of Mbarara. After two hours of driving it broke down in the middle of nowhere. I was then crammed into a Toyota with seven others and two babies. The car had only four seats.

A month later I finished my work at the children’s hospital and caught my final bus to Kampala. I didn’t escape unscathed: protesting taxi drivers closed the only road to the capital city, with traffic stopped for at least two kilometers. I had to walk the entire stretch in a torrential downpour to find a bus on the other side of the jam. I was full of mud and my Oakley luggage bag was the only item that resisted the rain. Everything else was soaked.

This trip left me very tired. I woke up on the airplane face-to-face with a flight attendant who was watching me drool on my shirt. But I didn’t care. I slept damn good.

The good news is that we did have a video camera on the climb. The bad news is that my Ugandan guide forgot to press the record button while I was skiing. It was quite the surprise when I returned to camp and reviewed footage, but that kind of B.S. is all part of the experience.

This is the last of the three-part series about skiing Uganda for charity. If you like the story and adventure, then please help Uganda’s children and donate to Holy Innocents Children’s Hospital at http://www.snow4innocents.org/donate. This charity was made possible by Oakley, Children’s Hospital and Research Center Oakland, ACG, IonEarth.com, and the Vancity Buzz.

Comments