The inclusion of halfpipe and slopestyle skiing in the Winter Olympics ushered park skiing into a new era, bringing with it polarization and heated debate. While skiers still slide on snow and the sport’s fundamentals remain intact, the second cycle of freeskiing’s Olympic inclusion begs for reflection. Laying aside the competition vs film debate that takes center stage in most discussions, we sought to dig deep into the zenith of competitive skiing, to see what it really takes to reach the Winter Olympics and how the games have changed the sport.

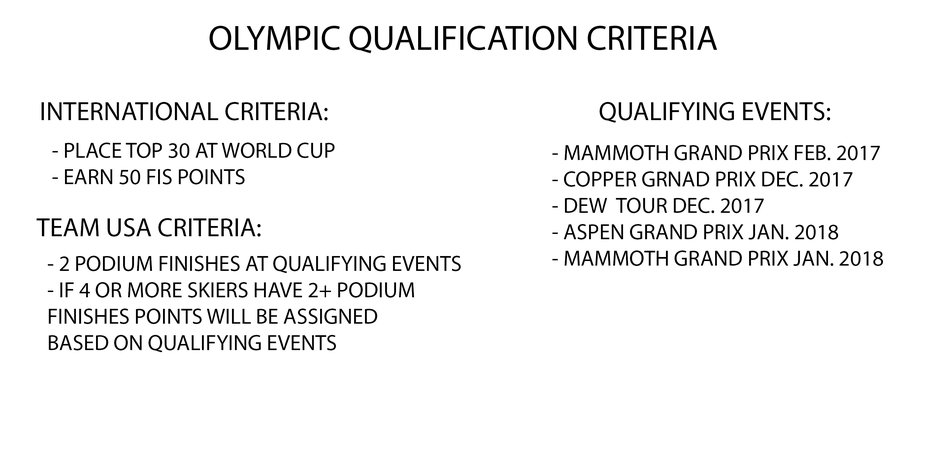

In order to qualify for the Olympics in either halfpipe or slopestyle, a skier must have amassed 50 FIS points, and have placed in the top 30 at a World Cup. Going into the 2017-2018 winter, there were 46 American skiers that have already met this minimum international standard, and another 16 who have met one of the two standards. In South Korea this February, there are a maximum of 12 spots total allotted per country between halfpipe and slopestyle. 4 to men and 4 to women in each. For the USA hopefuls, points and podium finishes decide these chosen few, while other counties have their own standards. However, the path to Pyeongchang starts long before the collection of requisite points. These skiers have put in years of work and thousands of dollars to reach even the precipice of Olympic selection.

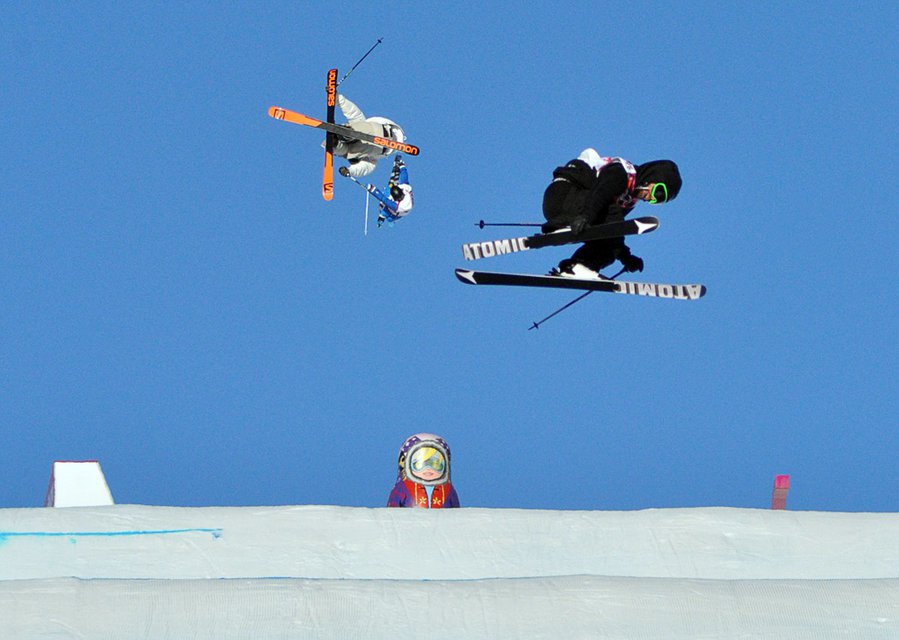

Photo: Ethan Stone

Needless to say, skiing is not a cheap leisure time activity but training and competition adds a whole new level of financial burden. Young skiers can join freestyle teams as young as 8 years old for many clubs, beginning a structured skiing regimen with a defined pathway all the way to the Olympics. Programs like Park City United or the Steamboat Springs Winter Sports Club and can cost upwards of $5,000 per year, not including the cost of travel, contest registrations, and season passes. These clubs are not outliers in their price either, they are the norm.

A skier who trains and competes with a ski club from age 8 to 18 can expect to pay more than $36,000 in club fees alone.

By the time a skier is in their teens, the sum of these costs can be upwards of $10,000 a year. A skier who trains and competes with a ski club from age 8 to 18 can expect to pay more than $36,000 in club fees alone. Alternatively, young skiers may attend a ski academy such as the Burke Mountain Academy or Sun Valley Community School, where tuition and boarding can cost more than a private university, coming in at $55,000 per year.

It is difficult to fault skiers for chasing podium dreams, especially when competition is still the most defined path to establishing a career in skiing, the cost of this journey, however, is huge. Assuming a skier reaches the Olympics at age 21, it is safe to assume that they have invested well over $150,000 to reach that point, and that’s before factoring in necessities such as housing, food, and everyday needs.

There are scholarship programs and other measures that skiers take to mitigate the costs of competition, however, the financial burden lies almost entirely on the parents and families of these young skiers. While money begets skiing in general, the astronomical costs of competition are pushing Olympic dream farther out of reach. Money and support from sponsors and organizations like the US Freeskiing Team and sponsor can help more established skiers pay their way through the competition circuit, however, it takes years of training and resume building to reach that level. Skiers from countries without that support face an even tougher road.

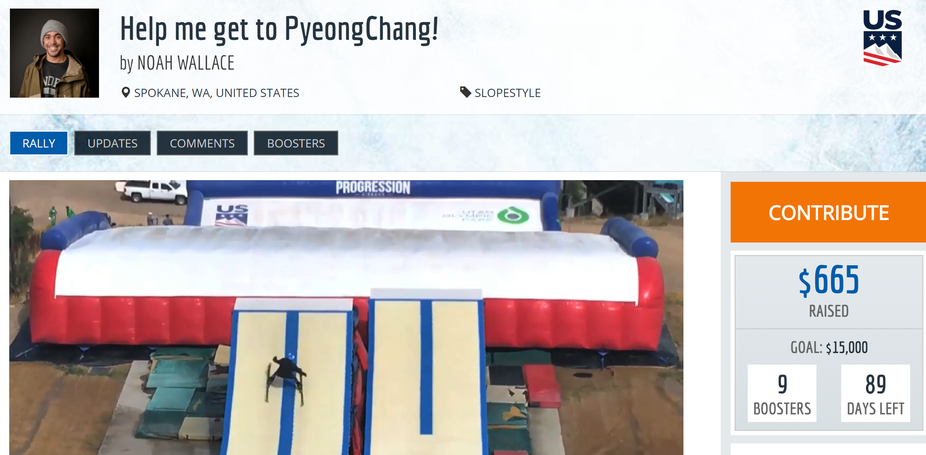

Given these monetary struggles, many skiers have been turning to alternative fundraising outlets including crowdfunding campaigns. In the lead-up to the 2014 Sochi Olympics, Canadian skier Matt Margetts turned to crowdfunding to raise money when changes to the national team budget left him short $20,000. At the time of launching his campaign, Margetts was ranked 2nd in Canada, and 11th in the world. He raised the money, made the trip, and placed 15th in Sochi. Slopestyle skier Nick Goepper, who took home the bronze medal in the 2014 Sochi Olympics gave a similar estimate for the cost of competing for a season, $20,000-25,000, adding that the majority of these costs are paid by sponsors, not the national team. The USSA even has it's own dedicated crowdfunding platform. With costs like these, it’s easy to see why many ski companies are pivoting away from competition skiers and investing in relatively lower cost content projects.

The problem arises when FIS requires a dozen memberships, has national team obligations, regulates what sponsor logos can be shown in competition, and has events in hell-and-gone parts of the world and nobody can get to.

Goepper continued to discuss how it is key to pick up sponsors early in your career, and how grassroots competitions are key to the sports health overall. He explained saying, “ I think the cost of SKIING keeps talented skiers off the mountain. This is an expensive sport. As far as competing goes, I think your skill, contest results, and overall influence are related to how much support you get from sponsors. Usually if you hit the sweet spot of having a breakout year in your teens and get some results, and get picked up by a few sponsors, getting around the globe to compete shouldn’t be a problem. The problem arises when FIS requires a dozen memberships, has national team obligations, regulates what sponsor logos can be shown in competition, and has events in hell-and-gone parts of the world and nobody can get to. Grassroots events, open events, and core events like X Games and Dew tour are important for keeping our sport alive and well.”

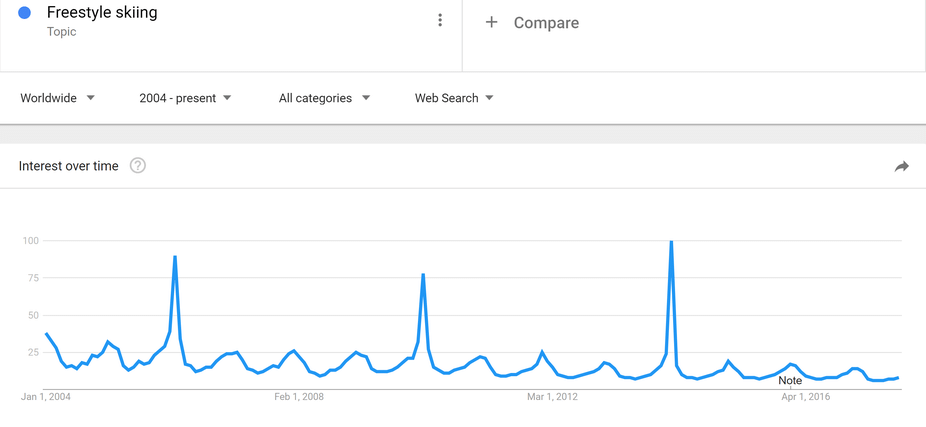

The popularity of freestyle skiing according to Google

Many argued that the inclusion of halfpipe and slopestyle would bring more exposure and money to the sport, six years and on the eve of freeskiing’s second Olympics, that is clearly untrue except in a minority of cases. While there may be a spike in interest and a couple outliers may cash in, money is more thinly spread than ever. Macro trends like the democratization of content, an increase in the access to training tools that level the playing field, and climate change have made a far greater impact on the distribution of money in skiing than what little new worldwide exposure the Olympics may provide.

Are the naysayers correct in painting the Olympics as a greedy quest to line the pockets of the organizing bodies? Have the “pipelines” that these bodies have laid out blinded skiers from the motives that founded the sport? Have the Olympics helped to price out up and coming skiers from a sport with already high barriers to entry? These questions remain, with merits on all side of the discussion. What is certain is that reaching the highest stage of skiing competition requires a huge investment, with the bulk of the burden placed on the skiers themselves and their families.

Comments