"FAME! 'NEIN! IT'S MINE!' IT'S JUST HIS LINE, TO BIND YOUR TIME, IT DRIVES YOU TO CRIME ..."

- David Bowie, 'Fame'

Rick Sylvester jumping into history off the cliff face of El Capitan in Yosemite National Park. Photo courtesy of Mike Marvin.

Rick Sylvester jumping into history off the cliff face of El Capitan in Yosemite National Park. Photo courtesy of Mike Marvin.

On January 30th, 1972, a subversive camera crew looked on as a man in a one piece stretch ski suit, crash helmet, and red parachute pulled the anvil out of his gut, pointed his skis towards the towering cliff face of Yosemite’s El Capitan, and cannon balled himself into the annals of history. This human blur barreling towards the canyon lip - on his way to attempt the world's first filmed ski BASE jump - went by the name of Rick Sylvester.

Committing himself to the impossible, Sylvester would launch off of the 3,000 foot drop with his life depending on a self-release system the film team designed to kick the skis from his feet. If it failed, the dare devil’s death was almost certain. Sylvester had less than 56 airplane jumps under his belt and had yet to define himself as an expert skier, yet his reflexes were sharper than Formula 1 racing legend Nicki Lauda, and he had the brass balls to back them up with proper daring. By the time night had fallen on Yosemite Valley, he would be famous.

The El Cap jump had been a meticulous exercise in subterfuge, engineering, cunning, and intelligent design, one that took a more sinister edge when the park service repeatedly refused the group’s applications for permits to do the jump legally. “I recall the adrenalin rush that seemed unabated and the fear that the park department would catch us… true fear,” recalls modern Hollywood writer, director, and producer Mike Marvin, who would go on to make Hot Dog! The Movie after catching this world-record stunt on film in his salad days.

The imposing 3,000-foot cliff face of Yosemite's El Capitan towering to the left of Half Dome. Photo courtesy of Mike Marvin.

The imposing 3,000-foot cliff face of Yosemite's El Capitan towering to the left of Half Dome. Photo courtesy of Mike Marvin.

“We planned on a full moon for the most night light possible in the Sierras. From the start, everything was in secret-even the rental of the Jet Ranger helicopter that we used to ferry almost a dozen people and a ton of gear. The camera crew consisted of Reed Smoot and their three or four guys. I was there. Henry Diltz was there. Bob Stokes and Dick Tash. And, of course Rick, accompanied by a friend of his named Steve Engle.

It was Rick’s friend Steve who located a suitable takeoff spot where there was enough snow to build a jump. This was above the Wall of the Morning Light. Rick was such an asshole that he jammed it in our faces that his Beverly Hills friend found the perfect site to build the jump as opposed to us with all the experience. I knew we were going to be in trouble with this man, sooner or later.”

While far from an expert skier, Sylvester had the nerves of a Formula 1 racer. Here he practices with his full BASE jumping kit prior to the jump-you can see the custom release device strapped to his calf. Photo courtesy of Mike Marvin.

While far from an expert skier, Sylvester had the nerves of a Formula 1 racer. Here he practices with his full BASE jumping kit prior to the jump-you can see the custom release device strapped to his calf. Photo courtesy of Mike Marvin.

The filming of the 1972 El Capitan ski BASE jump sequence is one that has lain shrouded in both mystery and obscurity for over forty years, and one that involved a wild cast of characters. Marvin himself, who's cult classic Hot Dog! The Movie was in fact his 5th ski film after a raucous journey through the heart of the 70's to establish his name as a ski documentarian was abandoned, grew up as a Squaw Valley boy, and would return to his home ski turf much later in life to shoot what would become the most commercially successful Hollywood ski movie of all time. Bob Stokes, another Squaw ski bum, was his production partner, while Henry Diltz, who would go on to produce world-famous photographs of rock legends from Neil Young to Mick Jagger, would assist as a cameraman.

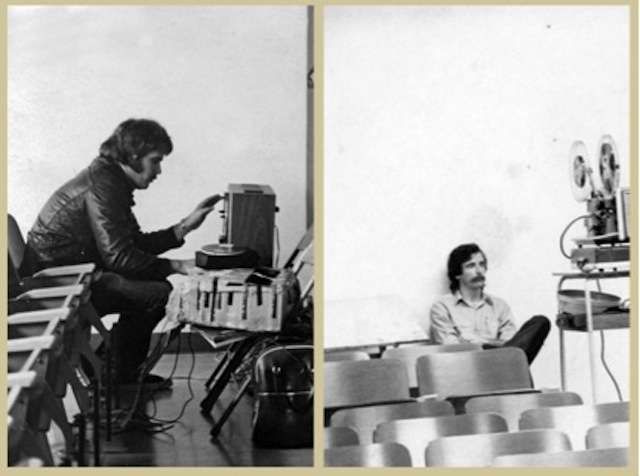

Mike Marvin (left) and Bob Stokes (right) in the early days of their film careers. Photo courtesy of Mike Marvin.

Mike Marvin (left) and Bob Stokes (right) in the early days of their film careers. Photo courtesy of Mike Marvin.

Another would be Reed Smoot, a cinematographer who later won an Academy Award for his 1973 documentary, The Great American Cowboy. Reed Smoot’s grandfather, the ordained Mormon apostle turned United States senator of the same name, was pivotal in legislation that created the National Park Service: the very same organization that would have arrested this rebel film band had they been discovered. With a talented crew of future stars in full support, the team committed themselves to their outlaw mission under the struggling light of a low winter sky.

Part of The Earth Rider crew. From left to right: Rick Sylvester, Dick Tash, Bob Stokes, and Bill Leaky. Photo courtesy of Mike Marvin.

Part of The Earth Rider crew. From left to right: Rick Sylvester, Dick Tash, Bob Stokes, and Bill Leaky. Photo courtesy of Mike Marvin.

“The last chopper load came and went about two hours before sundown, and was scheduled to return the next day for the shoot. The sky was clear as far as the eye could see. It seemed the weather would hold. Stokes, Tash, and I belayed ourselves into a rotten cedar tree and began the long process of building a jump in total moonlight.

At about ten or eleven, we broke for dinner and everybody ate and those who weren’t working went to sleep in their tents. We maintained complete radio silence, and kept fires to a minimum. We kept our voices down even though it was 3,200 feet to the valley floor. Voices carry over that sheer granite and often you can hear the climbers calling out to one another on El Cap. So we remained muted.”

Rick Sylvester steps out the in-run to the El Cap jump. Photo courtesy of Mike Marvin.

Rick Sylvester steps out the in-run to the El Cap jump. Photo courtesy of Mike Marvin.

Along with Dick Tash (a starring ski athlete in the film, who among others would form what became known as the Aspen Rat Pack), this monkey wrench gang of film pioneers committed to the dark of night to take to their labor. They knew the stakes: it would be straight to jail if they were caught. The park service would cuff them all, no questions asked.

“We worked on the jump until about an hour before sunrise and then the three of us caught a little breakfast and a nap. The jump was scheduled at exactly 11 that morning. We synchronized our watches endlessly as the last chopper went out and returned. On the valley floor, we had two cameras with 10-minute loads of 16 millimeter film ready to roll with 500 millimeter lenses. On top, we had Smoot’s borrowed Éclair 16 millimeter camera and crew, who’d I’d paid out $1600 to help film this totally illegal stunt. I had my camera and Stokes had a camera. The chopper returned at 10 and we loaded Smoot and his crew aboard to get the big shot of Rick flying off the edge of the cliff,” Marvin said.

Up top, Sylvester would clip into his Spademan bindings before hucking off the enormous face of El Capitan, and once in mid-air, yank on the ingenious pull cord mechanism Marvin had fabricated himself, one that would provide a platform for later generations of ski BASE jumpers to evolve into their own designs. If it failed, though, Sylvester’s death would be almost certain.

Up top, Sylvester would clip into his Spademan bindings before hucking off the enormous face of El Capitan, and once in mid-air, yank on the ingenious pull cord mechanism Marvin had fabricated himself, one that would provide a platform for later generations of ski BASE jumpers to evolve into their own designs. If it failed, though, Sylvester’s death would be almost certain.

Click to Tweet this quote!

“What happened was as follows: the chopper took off at 10:45 and circled west away and up, then took a route straight up the valley. It made a tremendous amount of noise, and at that point it became obvious that radio silence was never necessary since the chopper had surely blown our cover already. Too late; at 11, the cameras on the valley floor started rolling, focused on the jump from which we had rolled out a huge orange banner to mark the spot. There was no way to miss the shot… as long as Rick actually did it. But he did not.”

The original cue had been 11 a.m. sharp. Maintaining absolute radio silence while Reed Smoot slowly circled out of position with the Jet Ranger spinning its rotors in the frigid air, the team nervously awaited a signal for a go.

“He lost his nerve at the last second and refused to jump,” Marvin comments. “Meanwhile, the chopper was flying in circles in sub-zero temperatures. One of the two cameras aboard froze and went down. That left Smoot on the Éclair and me on the ground. Stokes was positioned below the jump, waiting for a cue.”

With cameras trained on the jump spot, the crew began to lose their nerve as Sylvester refused to jump. Photo courtesy of Mike Marvin.

With cameras trained on the jump spot, the crew began to lose their nerve as Sylvester refused to jump. Photo courtesy of Mike Marvin.

While the film team ground their teeth wondering if their precisely orchestrated, wholly illegal shoot was a flop (then wondering who was going to step up and risk the jump while they still had light, should Sylvester not jump), twenty-four minutes past the planned jump time, Sylvester found his courage and turned his skis towards the lip of El Capitan. He gained speed quickly as he stared into the abyss of the valley.

“We were screaming at Rick to go. He just shook his head ‘No.’ Screaming and screaming. Same response: ‘No’. Finally, after 24 minutes of gathering his courage, and without warning, he pointed his skis down the ramp.”

24 minutes after the scheduled launch, Sylvester boosted into Yosemite Valley, and into history. Clip from the original film sequence courtesy of Mike Marvin.

24 minutes after the scheduled launch, Sylvester boosted into Yosemite Valley, and into history. Clip from the original film sequence courtesy of Mike Marvin.

Sylvester boosted straight off the top of El Cap and began soaring into space as the fierce winds that day knocked him around. The crew took their first breath as he engaged the binding release cords successfully, exhaling only as the skis fell below and Sylvester’s chute emerged in a plume of blue and yellow fabric in Yosemite Valley.

Sylvester flying around the serene Yosemite Valley. Photo courtesy of Mike Marvin.

Sylvester flying around the serene Yosemite Valley. Photo courtesy of Mike Marvin.

The world’s first ever ski cliff BASE jump was a success. Yet to the film team’s standards, the shot would not be the ground-breaking visual they had envisioned placing them on the map of the extreme sport film making fold.

“I caught his descent totally, but Stokes never knew he was coming,” Marvin offers with a tone of dissatisfaction.

“Smoot had him, but the chopper was so far away that all we saw on film was a dot fly off the edge. We knew we had missed the shot. We knew it would have to be done again."

Rick Sylvester comes in for a landing after successfully pulling off the first BASE jump in skiing history. Photo courtesy of Mike Marvin.

Rick Sylvester comes in for a landing after successfully pulling off the first BASE jump in skiing history. Photo courtesy of Mike Marvin.

In a Ski Magazine article originally published in 1973, which made little reference to the larger full feature film attached to the feat, Sylvester gave his perspective of the jump. "An 80 foot pine came first, snatched me out of the air, and tangled the chute's lines into a spider web. I, a spider in Langes, descended brittle branches. Except the last 20 feet, where there were none. Bear hugging. And then it was mercifully over.

Epilogue: the film results were terrible. Two weeks later, the jump was repeated, with great cinematic success. But that's another story."

Rick Sylvester's first ski cliff BASE jump was ripe with danger. His narrow brush with impaling himself on an 80 foot pine tree kept his wits on edge all the way to the end. Photo courtesy of Mike Marvin.

Rick Sylvester's first ski cliff BASE jump was ripe with danger. His narrow brush with impaling himself on an 80 foot pine tree kept his wits on edge all the way to the end. Photo courtesy of Mike Marvin.

Having bounced down the trunk of this towering pine, Sylvester quickly scooped up his chute and cords as the heli landed. Boarding the helicopter elated by the success of this feat, the Jet Ranger's rotors spun furiously to climb the crew out of the valley, escaping the sight and ear shot of the park service of America's most famous national park. Yet even though they'd evaded capture and successfully pulled off the first filmed ski BASE jump in history, the mood was far from relieved.

When we got the footage back, which weren’t the perfect A-grade shots we were hoping for, is when infighting began in earnest. Sylvester took zero responsibility for his loss of nerve. Period. He laid it off completely on me with the words: ‘ We could’ve used radios! You fucked up!’ Forget that Sylvester agreed with radio silence. That started the war.

Click to Tweet this quote!

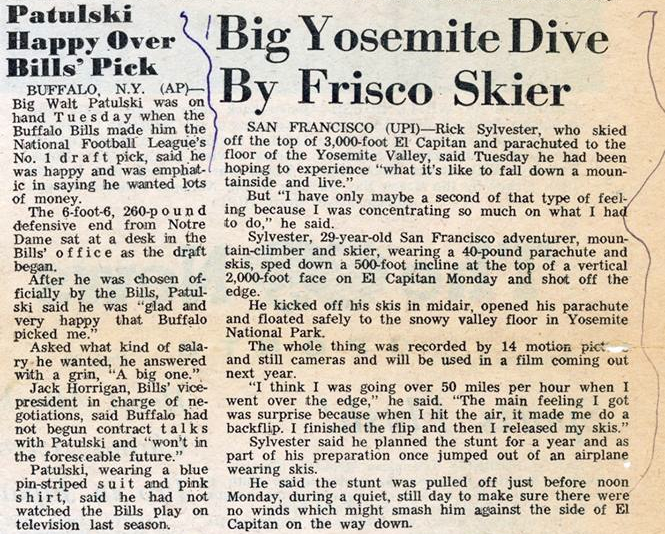

A clip from a February 1972 edition of The News highlighting the El Cap jump.

A clip from a February 1972 edition of The News highlighting the El Cap jump.

Though Marvin had been the original directing and producing vision of the first ski BASE jump in history, by the dawn of the MTV generation, few would recognize his pivotal role in the birth of extreme skiing, much less the timeless film that managed to slip between the cracks of cinematic history. The film, Earth Rider, would go on to essentially feature the birth of extreme skiing, with Sylvester’s jump as the keystone stunt.

Yet by decade’s end, it would be all but forgotten. Despite the world’s first-ever ski BASE jump being a technical success and an extraordinary achievement in its own right, the little war that brewed among the cast of characters that brought the feat to completion would have far reaching consequences.

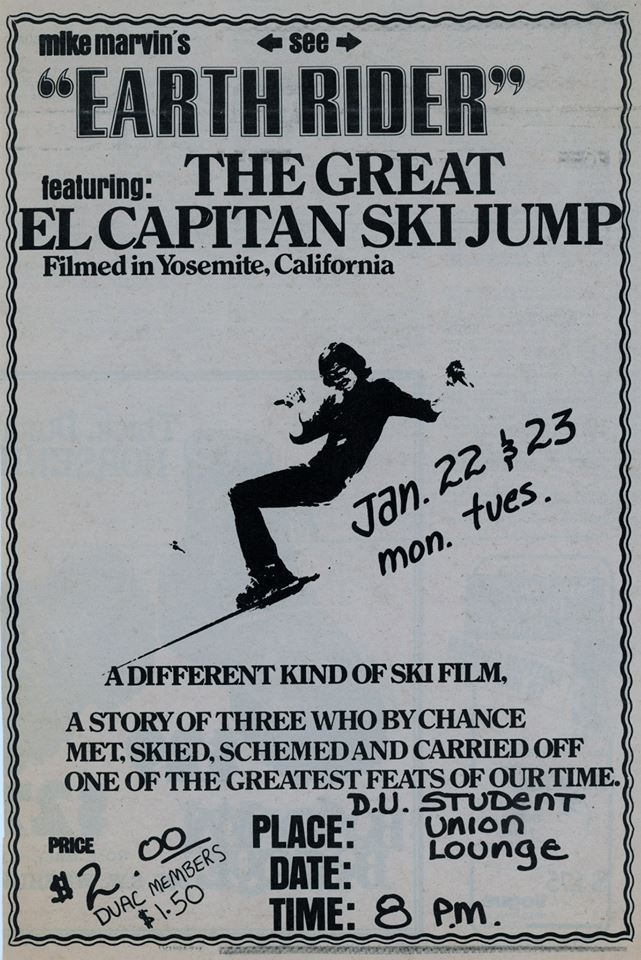

The poster art for Mike Marvin's legendary 1972 'Earth Rider' feature.

The poster art for Mike Marvin's legendary 1972 'Earth Rider' feature.

The mystery over the very existence of this footage, the story of the visionary Earth Rider film, the filmmaker, his abominable film brawls, and the further secrets of the saga that would ultimately lead to the raucous mega-million ski film hit that was Hot Dog! The Movie will be continued in the next installment of Hot Dog! The Legacy...

lionel

July 22nd, 2014

Sweet telling, Christian!!!!

Rick Sylvester

April 8th, 2015

Great piece. Of course it could have been a lot better if more of it were true. The amount of falsehoods and distortions contained within is huge, truly staggering. It’s essentially a hit piece. Due to its source I believe—no, make that know—it to be deliberate. And I intend to take appropriate measures.

Christian W Dietzel

April 8th, 2015

“There’s three sides to every story. Your side, my side, and the truth. And no one is lying. Memories shared serve each differently.”

- Robert Evans, from ‘The Kid Stays In The Picture’

Rick Sylvester

April 10th, 2015

Sure, buddy boy. But aside from the cute-icisms, I was well aware of what you’re alluding to, trying to rationalize via, way before you were born. Back then, probably in the Sixties, and this is also way before Evans’ book was penned, I saw “Rashoman” one of Kurosawa’s great classics. It deals with the theme in question. And psychologists even coined a term based on the film for the syndrome, the “Rashoman Effect”. Despite this, there nevertheless is a thing called truth. And it is often the case that its opposite is not the result of a faulty memory. Now this may come as disturbing or shocking to you but unfortunately there are people who do not tell the truth, and who do so deliberately, in some cases as they see it serving them. And it is also not all that unusual thet they may use others who oftentimes have absolutely no direct of firsthand knowledge of what they’re being told, to help and further serve their ends. We might call these people “dupes”. or even “willing dupes”.

Gacha Life

August 1st, 2020

Gacha Life 2 is popular role-playing game released for Android, iOS, and Microsoft Windows Operating system.

Gacha 2

Rick Sylvester

August 1st, 2020

To attempt to correct the errors, a large proportion deliberate, in this article. a successor to a previous one by the same author, but even more so, and essentially a hit job, would be longer than the piece itself which should be read as mostly fiction. My El Cap jumps project was a very positive and successful venture including the fact of my not losing my life which for some odd reason also seemed important. The one negative of the entire experience—well actually there were two but the other one was relatively minor—was my association with Mike Marvin. And for that I blame myself. Certain characteristics of this person strongly remind me of the current inhabitant of the White House, hopefully not much longer although every day feels like an eternity, namely malignant narcissism and pathological lying. I think they’re both sick. In Dietzel’s one sided narrative, much of it based on interviews with Matvin and none with me, you won’t find anything about the lawsuit I won against Marvin over his stealing the original footage of the jumps which I’d paid for, the fact all the good usable footage came from the second jump which he had absolutely nothing to do with, thank goodness, yet over the years claimed credit for, and all the investors, not exactly wealthy individuals, who never saw a penny, whom I consider bilked. Just a lovely individual—a liar, cheat and thief as was proven in court. And it’s in the records.