In the ski industry, it’s not hard to find the usual smattering of upstarts trying to be the next big thing. On the same note, it’s not uncommon to learn that many of these companies outsource their supply lines to foreign shores, leaning on the manufacturing expertise, and cheaper costs, of more long-established players.

The Company

With so many fish trying to be big in a pond that just keeps getting smaller, some entrepreneurs and innovators are cultivating new approaches to the age-old craft. Graham Sparks is the epitome of this new wave of ski manufacturer. Injecting soul into his skis like a well-placed IV drip, Sparks has been quietly and methodically honing his craft in the sleepy backwater of Aspen, CO—not the most obvious redoubt for a craftsman, with its celebrities and pop-up champagne bars, but a place that’s certainly fed the main vein of ski culture in its time. With the bottom line secondary to his pursuit of excellence, Graham is redefining the template of what it means to design, build, and sell a sick setup.

High performance--higher art. Graham Sparks brings soul to his skis.

High performance--higher art. Graham Sparks brings soul to his skis.

From his unassuming workshop where a simple loft bed provides nightly relief from hours working with sandpaper and resin, Graham Sparks started Grizzly Boards three years ago. His first two winters were spent largely on research and development; dialing in construction and materials, personally testing each cut and shape until the feel was just right. By last spring, Sparks was confident that his skis could shred, so he began to develop the aesthetic that would eventually define his brand.

Contrary to the overwhelming horde of people trying to win a piece of the pie, Sparks does nearly everything by hand. With a solid foundation in carpentry taught early by his father, he has utilized his skills in building to move towards the goal of perfection.

What I'm doing is more of a craft. Everything is done by hand. Everything is inspected by me. All the graphics are hand painted. I have a couple different artists locally...It's a little piece of art. It's just trying to get the industry back to craftsmanship rather than just pumping out skis.

The Context

To understand what motivates a visionary like Graham Sparks, it’s important to understand how he came to be building skis in the first place. Originally from the flat seaside plains of Rhode Island, Graham grew up skiing with his family, chiefly his father, most every weekend. During his teen years, he dreamt of going to college, joining the Peace Corps, and eventually becoming a teacher. However, as is often the case, life had other plans.

During his college years, Graham’s Father Kenneth began having cognitive issues; he’d forget words or act oddly out of character. At first, the doctors believed it to be the early onset of Alzheimer’s, but a later diagnosis confirmed it to be Frontotemporal Dementia, a slow moving killer that strips personality, memory, and the ability to speak from those it afflicts. For the next six years, Graham, along with his mother and sister, watched as the man they’d known slowly slipped away.

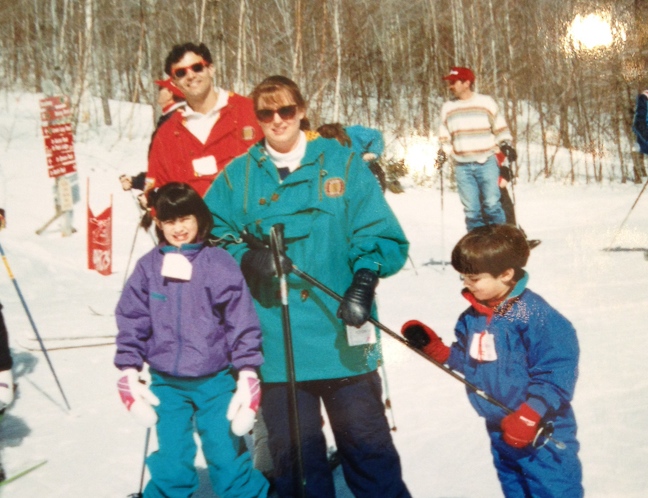

With lil' Graham front right, the Sparks family enjoys a ski trip in better times.

With lil' Graham front right, the Sparks family enjoys a ski trip in better times.

During his father’s long decline, Graham began looking for relief—some sort of distraction to break away from the pain. In between his sophomore and junior years of college, Graham found himself one day in his family’s barn, building pressure molds out of two-by-fours, making a rough attempt at building a pair of skis. He threw himself into the work, driven and possessed by a newfound passion that linked him, existentially, to the fading light of his father. “It was just a way for me to get out of my house and clear my head and turn my frustration into something real,” Graham said, looking back.

Graham’s first ski was, by his own admission, a total piece of crap. The tips were nearly a quarter inch thick. It didn’t flex—it was just a big ol’ chunk of wood. Yet, these early failures were only kindling for the fire, and upon every attempt, the skis got better.

During those early days, fresh from the garage and still covered in sap and sawdust, Graham would try to show his father what he’d built. He wanted to lift the veil that had fallen over his father’s eyes, but by that time, his dad was mostly gone. Holding aloft one of his recent creations, Graham hoped for a glimmer, a flash of recognition behind the glazed eyes. Instead, his father stared vacantly at the lifeless sticks in his son’s hands, pacing onward arbitrarily through the house, stumbling past family portraits from ski vacations long forgotten.

Turning powerlessness into purpose, Graham set into his first pair of skis in the family barn while his father suffered through Frontotemporal dementia.

Turning powerlessness into purpose, Graham set into his first pair of skis in the family barn while his father suffered through Frontotemporal dementia.

As his father’s condition worsened, Graham began burying himself deeper and deeper in this ski craft; the rest of his family similarly absorbed themselves in new passions as Ken Sparks declined further and further into dementia. His mother immersed herself in photography, and eventually started her own business. Graham’s sister had been successful in publishing in New York City, but the experience of taking care of her father all those years pushed her to change course as well, and she decided to commit to a new career in nursing, where she could take care of those in a similar state of suffering. Like a phoenix from the ashes, each family member emerged from that six-year ordeal transformed, but strengthened.

Once he took a turn for the worse--that's when I really started to put the time in. I'm sure subconsciously there was a connection because my Dad and I would ski every weekend together. But yeah, I don't know--It's weird to think about.

Spark’s path in life changed when on a whim he emailed a small ski manufacturer, 333, based in Mammoth Lakes, California asking for a job. Not expecting a reply, he was surprised when they promptly invited him out to California to do a ski-building internship and hone his skills. A month after that email exchange, Graham’s father passed away. Two weeks after that, he started his drive West.

Graham’s time apprenticing was a formative experience. He’ll readily concede that he didn’t find his dream in California, but he learned skills that would enable him to discover it eventually. In true bohemian style, the 333 crew had a traveling workshop trailer that they could park anywhere to build skis. He recalls fondly a promotional trip taken up Hwy 1 with 333, stopping often to practice the craft while overlooking the Pacific. The smell of ocean breeze contrasted well with that of epoxy and other industrial chemicals, causing Graham to undergo long periods ecstasy that were either induced by the scenery, the workshop, or perhaps both.

On the mend with the Mammoth-based 333 crew, Sparks eats up the sunset along the Pacific Ocean on Highway 1.

On the mend with the Mammoth-based 333 crew, Sparks eats up the sunset along the Pacific Ocean on Highway 1.

There, on the cusp of land and sea, Graham would often pour himself a hot brew while sitting on top of the trailer to enjoy the sunset. To an outsider, knowing that his dad had passed away only months earlier, one would assume that he carried a great sadness during those times. The truth was, Graham was filled with joy that his dad had finally found peace. His dad’s suffering, and the suffering of his family, was over. Sipping French-pressed coffee, soaking in the fading sun on that jagged coast, he felt free, pure and simple.

Graham later visited some family friends in Aspen for a Thanksgiving holiday. While there, he found a job tuning skis and a workshop that was up for rent. He signed up for both, and never looked back.

The Craft

Early rising in the shop, with accomodations just above the ski press.

Early rising in the shop, with accomodations just above the ski press.

On any typical day, Graham wakes up early. His breath illuminated by the beam of his headlamp, he rolls out of his workshop cot and puts the coffee on. Bleary-eyed from another late evening in the ski shop (his night job), he heads out on dawn patrol and is usually slashing pow before most of us are awake. Aspen—the legendary playground of the wealthy—has become an incubator for Grizzly Boards and Graham’s unique take on ski manufacturing. Combining his living space and workshop, Graham saves on rent by sacrificing domestic luxury for the merit of achieving his innermost dreams. In a very literal sense, Sparks lives, breathes, and thinks skis.

Graham wakes up—skis. He eats his morning cereal—skis. Comes back home from skiing—skis. There is nothing to interrupt his creative focus, and by default, he kicks ass at what he does.

Graham Sparks rips the backcountry on a self-made setup.

Graham Sparks rips the backcountry on a self-made setup.

In contemporary mountain culture, there is a lot of talk about how “core” someone is. What cliff was hucked, how gnarly the line was, last call-first chair, blah blah blah. The truth is, few individuals can rival Graham Sparks in the realm of “core” criteria. The guy is a physical manifestation of what it means to be dedicated and passionate about skiing. He’s given his life over to his trade and personifies the bohemian that draws purpose and meaning from his craft.

To put it all in perspective, Grizzly Boards is a ski company that is client-based, meaning that when you order a pair of sticks from Graham, he’s going to make skis for you—himself. This manner of ski production is the inverse of what most ski companies do, making a broad assortment for different terrain and body types to saturate the market. Instead, Graham approaches his craft on an individual, humanistic basis. In his manufacturing progression, he’s certainly identified profiles that work well for certain types of people, but these are only guiding templates.

Graham Sparks honing his craft in his one-man factory in Aspen, Colorado.

Graham Sparks honing his craft in his one-man factory in Aspen, Colorado.

On the hill, Graham prefers a generous all-mountain cut. 98 cm underfoot, moderate rocker in the tip, none to speak of in the tail. Oftentimes, when a reliable powder forecast comes through the pipeline, Graham will start building a fresh pow setup. “Two to three days in advance of a storm, I’ll go to work on a new pair of skis, experimenting with shape and width,” Sparks explains, “Even for a big powder day, I always leave a little camber underfoot for stability for once you’re back on the firm stuff.”

In short, he's an artist.

I still learn from every pair of skis that I make. If I weren't learning, I'd be doing something wrong.

In many ways, Sparks is ahead of his time, or perhaps right on schedule. Most people in the mountains nowadays are craving that home brew authenticity. The buy local, shop local, eat green, regionally-sourced movement that is increasingly willing to open their wallets for quality. Sure, people are always going to order a PBR or Budweiser, but every year the market share grows for entrepreneurs such as Sparks who aren’t willing to sacrifice integrity for a profit margin.

Check out Graham Sparks' Grizzly Boards at grizzlyboards.com.

Olaus Linn

September 9th, 2014

Great piece Sam - inspiring and moving. Graham sounds like a badass.