tags:

Jackson Hole, Moose Wilson Road, WY, United States |

tetons avalanche |eric lovely avalanche |eric lovely |bridger teton avalanche center |avalanche accident

While we put up plenty of the best professional skiers and snowboarders in the world on the big screen, amongst our staff here at TGR hides a crew of seriously ripping darkhorse amateurs. Media Manager Eric Lovely is one of them. The 33 year old has been in and out of Jackson Hole since 2004, and joined our team two years ago. With the plan set to move to Denver to restart a career in renewable energy and to "be with my woman," Eric made his last (for now?) full season in Jackson Hole count, putting a full assault on the surrounding backcountry as you can see in his season edit above.

But that all came to a screeching halt when, on February 5th-one week into a truly epic month-long storm cycle-Eric was caught in a small avalanche and pinned against a tree. The experience, explained in his own words below, and the aftermath of that avalanche, have given him some serious perspective we can all benefit from as we eagerly await the first frost, first snow, and first mission out the gates. Here's Eric in his own words:

On February 5th, we went to a trailhead in Grand Teton National Park -Granite Canyon Trailhead-and skinned up 3,000 vertical feet on a really cold day that was hovering around zero degrees. It was sick, cold blower snow after it’d been snowing for a week into the infamous month-long storm cycle we had in February this year in Jackson. I was with a few friends, my brother, and my dad, who’s a great skier but who I’d never expose to terrain above his ability.

Eric shredding in the Jackson Hole backcountry before the avalanche.

Eric shredding in the Jackson Hole backcountry before the avalanche.

The plan was to ski the East face of a mostly treed run with a few openings . We skied a relatively open meadow at the top with awesome pow, and a little lower down we got into some small finger spines. We saw no snow or avalanche movement, and I believe that day that the Bridger-Teton Avalanche Center was calling for a moderate hazard.

The next zone that we got into, my friend Nate noticed a crack on the slope after he turned to stop. He made a hard ski cut from tree to tree, and nothing went off. I wanted to ski and film this line with two airs in it on an east/southest aspect, which was a fairly similar aspect to what we’d been skiing with no problem. Two people in the party skied down with no results, and a few moments after I dropped onto the slope, it cracked, and my friend yelled “Fracture!!” at me as I was taking off in the air. I saw the fracture below me in mid-air.

At that point, I was 100% focused on sticking my air and pointing it towards a tree, and I had all the confidence in the world that I’d be able to grab this tree I was headed towards. But the slide ripped my feet out from under me, and that was it.

I reached for the tree and got only pine needles, and got taken down. That was the first time I’d even been taken away by a slide, and as you can see in the video, while I was going down I was able to get my head above the slide for a moment. It took me down again, and I knew there were trees all around me, and I was trying to swim and grab at anything that might come by me.

I got slammed into a tree I didn’t grab for–it hit me-and it slammed me across the abdomen. And that’s when I felt the most intense pressure I’d ever felt in my life and I knew that I was getting crushed to death and that I wouldn’t last long.

I got slammed into a tree I didn’t grab for–it hit me-and it slammed me across the abdomen. And that’s when I felt the most intense pressure I’d ever felt in my life and I knew that I was getting crushed to death and that I wouldn’t last long.

I was left pinned to a tree on top of the snow. I had the wind knocked out of me and it was really hard to breathe, but my brother got to me almost immediately and dug out the snow from behind my pack, and I was free. I could stand up, my brother who used to be a volunteer ski patroller did a spot check for pain, and I wasn’t bleeding or having any specific points of pain, and I was missing a ski.

We looked for my ski for a minute, but I really felt we shouldn’t be spending any more time up there than we needed to. My brother traded me his two skis for my one, and we still had 1,500 vertical feet of skiing and two miles of bushwacking to do to get back to the car. It didn’t take too long, but when I got back to the car, I just felt like I needed to go home and rest.

But after a family conversation, and knowing I had insurance, and knowing how much pressure my abdomen had endured, I knew I should get it checked out. So I went to St. John’s Medical Center in Jackson, about thirty minutes away.

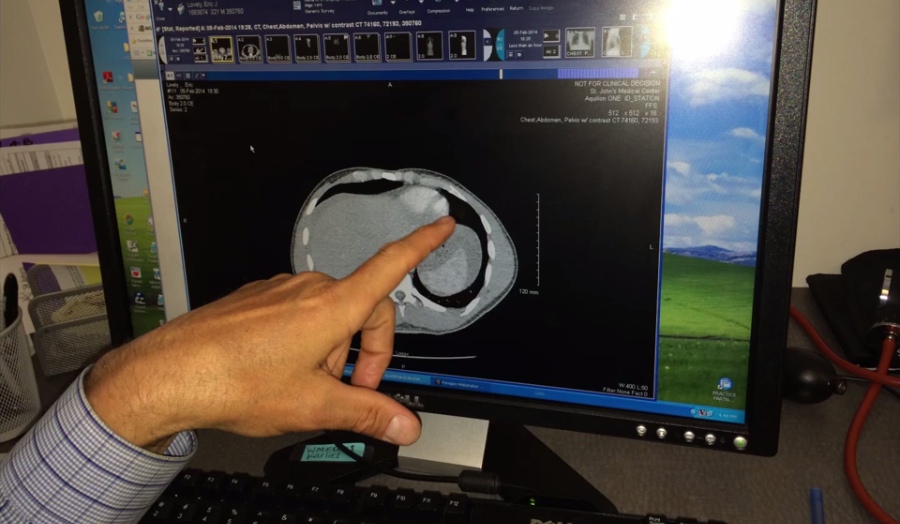

They did a standard CT scan, and told me I had a ruptured spleen, and didn’t act like it was so bad, but still wanted me to go to Idaho Falls as soon as possible. They started giving me blood because I had to wait for air travel, and my father came with me in the fixed-wing plane to Idaho Falls, and we got there to the hospital at about six pm. When we got to Idaho Falls that night, as soon as we arrived, it turned into an emergency situation, and all of a sudden, time was of the essence.

The next 24 hours were like a scene out of ER. The doctors said I had to go into surgery right away, off of a sudden saving my spleen was not a possibility. I went under general anesthesia, and they removed the spleen right then. The next morning, after the operation, I sat up and immediately passed out and lost consciousness. The doctors were yelling that they were losing vitals and that they didn’t have my pulse. I felt really weak and thought I was dying right then.

The next time I woke up, I didn’t know what day it was. An artery had re-opened-that’s why I’d passed out-and the doctor told me I’d had a “full oil change” – 15 pints of blood (the human adult male only has 10-12), plus plasma, plus they’d had to take out 16 centimeters of my colon.

Eric days after his accident in the midst of a nine-day hospital visit.

Eric days after his accident in the midst of a nine-day hospital visit.

I was in the hospital for nine days. It just ended up being way more intense, overall, than I would have ever expected the way I felt after surviving that avalanche. I have a scar that’s about 12 inches.

Don’t discount any avalanche warning signs. Part of the reason I’d discounted that crack we’d seen was because we’d already skied a thousand feet on that aspect and it had been totally fine.

Make sure you have people who can help you if you do get caught in a situation. Not just how to use your beacon-how to check for breathing, how to assess injuries-your partners need life-saving skills in addition to avalanche skills.

Get insured. And donate blood.